It was designed as an impregnable deep-freeze to protect the world’s most precious seeds from any global disaster and ensure humanity’s food supply forever. But the Global Seed Vault, buried in a mountain deep inside the Arctic circle, has been breached after global warming produced extraordinary temperatures over the winter, sending meltwater gushing into the entrance tunnel.

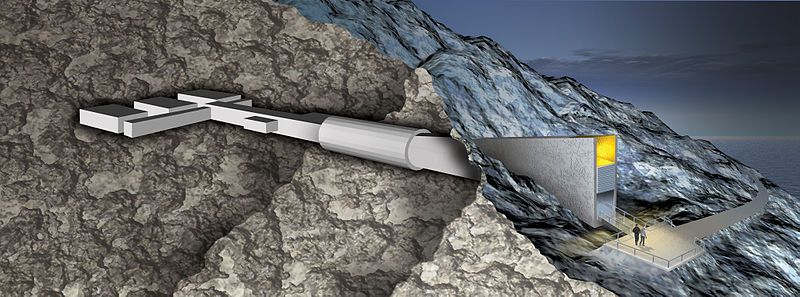

The vault is on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen and contains almost a million packets of seeds, each a variety of an important food crop. When it was opened in 2008, the deep permafrost through which the vault was sunk was expected to provide “failsafe” protection against “the challenge of natural or man-made disasters”.

But soaring temperatures in the Arctic at the end of the world’s hottest ever recorded year led to melting and heavy rain, when light snow should have been falling. “It was not in our plans to think that the permafrost would not be there and that it would experience extreme weather like that,” said Hege Njaa Aschim, from the Norwegian government, which owns the vault.

But the breach has questioned the ability of the vault to survive as a lifeline for humanity if catastrophe strikes. “It was supposed to [operate] without the help of humans, but now we are watching the seed vault 24 hours a day,” Aschim said. “We must see what we can do to minimise all the risks and make sure the seed bank can take care of itself.”

The vault’s managers are now waiting to see if the extreme heat of this winter was a one-off or will be repeated or even exceeded as climate change heats the planet. The end of 2016 saw average temperatures over 7C above normal on Spitsbergen, pushing the permafrost above melting point.

“The question is whether this is just happening now, or will it escalate?” said Aschim. The Svalbard archipelago, of which Spitsbergen is part, has warmed rapidly in recent decades, according to Ketil Isaksen, from Norway’s Meteorological Institute.

“The Arctic and especially Svalbard warms up faster than the rest of the world. The climate is changing dramatically and we are all amazed at how quickly it is going,” Isaksen told the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet.

The vault managers are now taking precautions, including major work to waterproof the 100m-long tunnel into the mountain and digging trenches into the mountainside to channel meltwater and rain away. They have also removed electrical equipment from the tunnel that produced some heat and installed pumps in the vault itself in case of a future flood.

Aschim said there was no option but to find solutions to ensure the enduring safety of the vault: “We have to find solutions. It is a big responsibility and we take it very seriously. We are doing this for the world.”

“This is supposed to last for eternity,” said Åsmund Asdal at the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre, which operates the seed vault.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.Thomasine F-R.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uAl8dSpkNWs

- I am on Svalbard, an archipelago 800 miles from the North Pole. 2. There are polar bears and glaciers and also the most amazing genetic library I have seen. 3. If you’ve never heard the Svalbard before, it’s this place right here. 4. Waaay up there on top of the planet. 5. It’s far away from civilization but Svalbard might be one of the most important places in the world. 6. It’s really cool and we get to go inside. 7. The place in charge of protecting the future of our food. 8. You know, this is quite simply a hole in the mud. 9. In there you have actually 13,000 years history of agriculture. 10. It’s quite amazing! 11. That’s Murray Haga – she is the Executive Director of the Crop Trust, the group that oversees the Svalbard global Seed Vault. 12. Inside that vault are boxes and inside those boxes? 13. Seeds. Quite simply seeds. 14. So normally somewhere between 300 and 500 seeds in these aluminum foils envelopes and that’s all there is. 15. Nothing else. 16. What is unique in Svalbard is that we collect seeds from absolutely all over the world or countries or institutions. 17. Choose to use this as a backup facility. 18. The main reason is so far north is because small bard is cold. 19. It’s got a permafrost – meaning the ground never really thaws even in the summer. 20. Most seeds can be stored long-term at minus 18 degrees or they can keep for a long time at the temperature that isn’t such cold either. 21.By digging a 130 meter tunnel deep into the mountain the vault is underneath that permafrost meaning they only had to cool it the remaining 12 Celsius. 22. At that temperature the eight hundred and sixty thousand varieties currently in the vault can be held for decades. 23. Some wheat varieties could last a thousand years! 24. But aside from serving as a backup for the global food machine the sea ball also represents something else. 25. A genetic library of evolutionary successes. 26. Wheat originates in well certainly the Middle East. 27. Now we grow wheat absolutely all over the world. 28. The thing is that it has taken many thousand years for these plants to move around the globe. 29. The challenge these days is really that the climate change is so fast so the plants are not able to adapt. 30. And that is really the fundamental challenge for agriculture these days and we need to help these plants to adapt faster. 31. That is why we need to introduce, for example, genes from a wild relative that can make sure that we can grow in funny climates with, for example, less water or that it’s able to fight a new disease that stems from climate change. 32. So scientists are traveling the world to gather more seeds and bring those into the vault,

Залишити відповідь